Jackie Perkins and Rufus Isaacs

During blueberry harvest, we see fields filled with blueberries weighing down the shoots of bushes. But how did those berries develop through the season, and what is the role of pollinators in berry development?

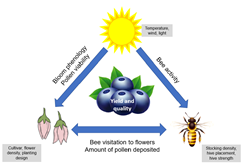

Bees are essential for helping these fruits grow into harvestable berries. During bloom, bees need to visit blueberry flowers to transfer pollen from the male part of the flower (stamen) to the female part (pistils or stigma). The pollen then germinates, and the pollen tubes grow up the stigma and into the ovaries. If the pollen is compatible and weather conditions are suitable, this results in fertilized ovaries that develop into seeds. These release hormones that trigger the swelling of the berry into a large and ripe fruit. Flowers that receive adequate pollination have more success becoming berries (we call this percent fruit set), and these berries are larger than those that received fewer pollen grains deposited by pollinators. With blueberry yield being so dependent on the movement of pollen, growers are very interested in maximizing the pollination potential on their farms.

How do we know that a field has reached its maximum potential for pollination? Our research team in the Bees and Berries project has used meticulous methods to track individual blueberry shoots and their flowers all the way from pre-bloom through to harvest to answer this question.

Prior to bloom, we randomly selected 5 bushes along 4 transects to use for our pollination experiment. On each bush, 4 similar shoots were selected and flagged, and the number of flowers on each shoot was recorded. Each shoot was given a unique code written on the flagging tape so that it could be tracked throughout the season, allowing us to measure exactly how many flowers turn into harvestable fruit. Each shoot was assigned to receive one of the following treatments:

- Open. Flowers were able to receive pollination from bees.

- Closed. Flowers were covered with a mesh exclusion bag prior to opening to prevent insects from visiting.

- Full pollination. Flowers received pollination from bees, plus they were hand-pollinated 2-3 times during bloom to ensure full pollination of each flower. We collected pollen from the same fields and brushed it onto the stigmas of open flowers on these shoots.

This method allows us to measure the effect of pollination on fruit set and berry size to estimate the effects of pollination and the effects of the different management approaches to pollination. We can learn a few different things from comparison of the different treatments. For example, the difference between the closed and open treatments indicates the benefit of bees and other pollinators. The difference between open and full tells us if there is any pollination limitation occurring, where the bees available are not reaching the full pollination potential of the field.

Once bloom was complete, all shoots were covered with mesh exclusion bags to protect them from damage, pests, wildlife, or accidental harvest. Now that harvest is underway, we are returning to the fields to assess the pollination success of our different treatments using the following metrics:

- % Fruit Set – the percent of flowers that successfully became fruit

- Berry weight – the size of the berries

- Seed set – number of fertilized seeds present within ripe fruits

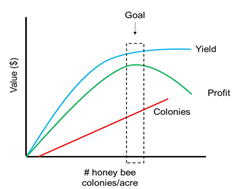

Using these methods, we can measure how well the fields in our research trials have been pollinated and use that information to compare the different honey bee treatments and determine the economic value of different pollination strategies. This winter we will have the results from these trials in Michigan, Oregon, and Washington farms and will be reporting the results back to collaborators and our regional blueberry growers.